According to an international team of scientists, the ancient monkey, known as Victoriapithecus, had tiny but remarkably wrinkled brain.

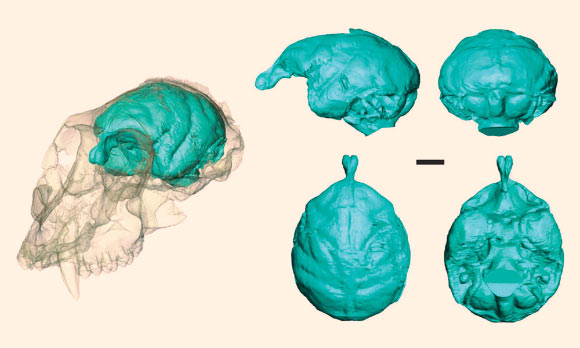

Brain of Victoriapithecus macinessi visualized for the first time using high-resolution X-ray imaging. Scale bar – 1 cm. Image credit: Lauren A. Gonzales et al.

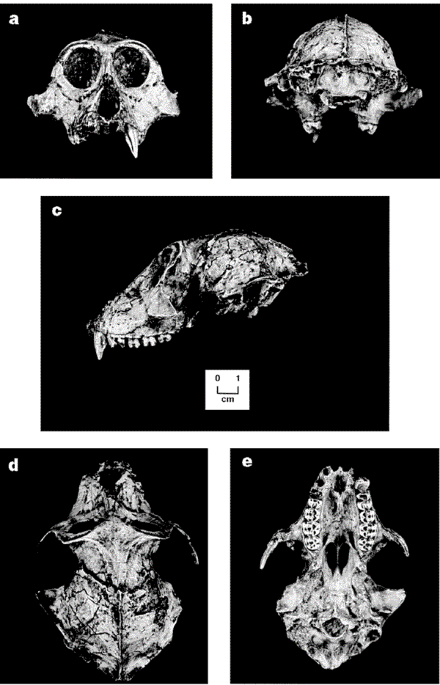

Victoriapithecus first made headlines in 1997 when its fossilized skull was discovered on Maboko Island in Lake Victoria, Kenya, where it lived approximately 15 million years ago.

As fossils from this era are rare, Victoriapithecus’ skull was one of the only clues to the early brain evolution of Old World monkeys. Before it was studied, paleontologists didn’t know if primate brains got bigger first and then more complex, or vice versa.

Thanks to high-resolution X-ray imaging, Lauren Gonzales of Duke University and co-authors have peered inside Victoriapithecus’ cranial cavity and created a 3D computer model of what the primate’s brain likely looked like.

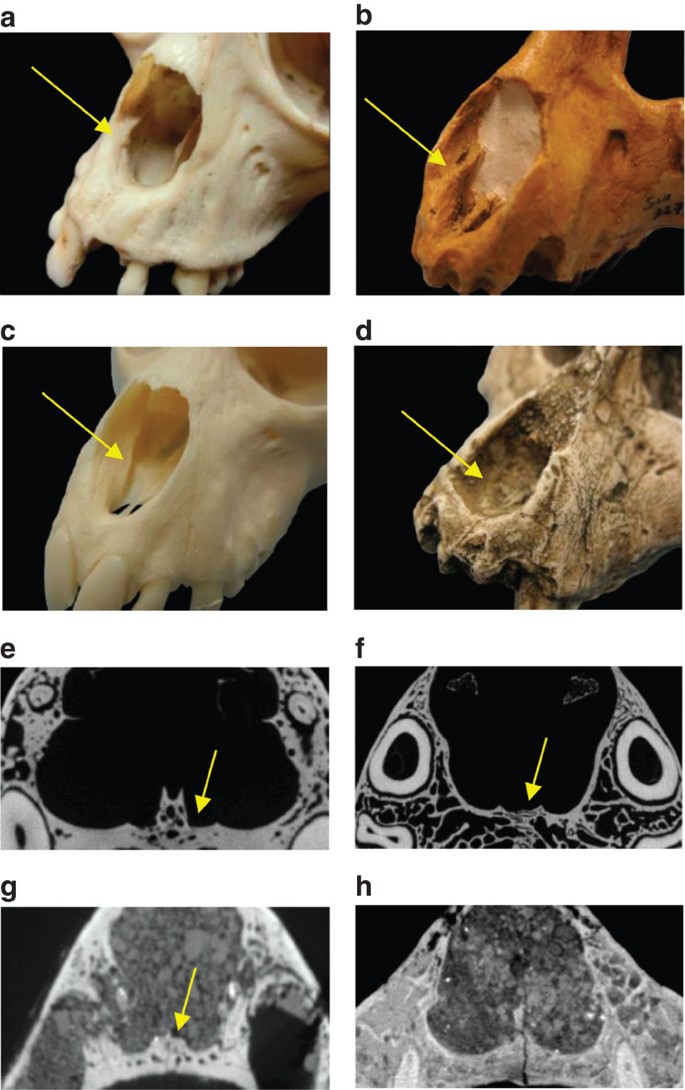

Micro-CT scans of its skull show that the monkey had a small brain relative to its body.

The scientists calculated its brain volume to be about 36 cubic cm, which is less than half the volume of monkeys of the same body size living today. If similar-sized monkeys have brains the size of oranges, the brain of this particular male was more akin to a plum.

Despite its puny proportions, the monkey’s brain was surprisingly complex.

“In the part of the primate family tree that includes apes and humans, the thinking is that brains got bigger and then they get more folded and complex. But this study is some of the hardest proof that in monkeys, the order of events was reversed – complexity came first and bigger brains came later,” said Ms Gonzales, lead author of the paper reporting the results in the journal Nature Communications this week.

The CT scans revealed numerous distinctive wrinkles and folds, and the olfactory bulb (part of the brain used to perceive and analyze smells) was three times larger than expected.

“Victoriapithecus probably had a better sense of smell than many monkeys and apes living today. In living higher primates you find the opposite: the brain is very big, and the olfactory bulb is very small, presumably because as their vision got better their sense of smell got worse. But instead of a tradeoff between smell and sight, Victoriapithecus might have retained both capabilities,” Ms Gonzales said.

The findings are important because they offer new clues to how primate brains changed over time, and during a period from which there are very few fossils.

The results also lend support to claims that the small brain of the human ancestor Homo floresiensis, whose 18,000-year-old skull was discovered on a remote Indonesian island in 2003, isn’t as remarkable as it might seem. In spite of their pint-sized brains, Homo floresiensis was able to make fire and use stone tools to kill and butcher large animals.

Source: sci.news